I’m writing this on January 1st.

The back door is open, blowing away the smoky air from last night’s fireworks along with the remnants of a slight hangover. In fact, it’s a beautiful Spring morning…

Now I’m not going to reminisce about the days when Winter meant rain, sleet and snow but it’s not right is it?

I don’t know if you have had chance to see the film, Don’t Look Up. It got panned by the critics, but I suspect that’s because it’s a bit blunt as allegories go, telling the story of how a couple of scientists try to persuade those in power that they have six months to act before a fatal comet hits the Earth. It is, however, a funny and depressing look at how our leaders and media fail to grasp the magnitude of the situation, and there’s a pretty blunt sideswipe at a character whose name might be Elon with a touch of Zuckerberg thrown in too!

After COP 26, I optimistically hoped we had turned a proverbial corner, but it turns out that worrying about the climate was something we did back in the Autumn but we’re on to something new now. Rob Parsons, editor of Northern Agenda, asked ten leaders what their hopes were for 2022. Amongst all the talk of levelling up and pandemic recovery, climate was mentioned only once in passing by one MP and once by Roger Marsh in order to explain why we needed more growth.

Meanwhile, I’ve just had a long email from West Yorkshire’s Mayor explaining what Mayoral plans are for decarbonising transport, ending with a paragraph on why it is important to allow the airport to expand so that we don’t ‘reduce our competitiveness compared to other regions’. I realise the grown-up thing to do is to compose a calm, well-argued email on the false narrative about displacement of air travel and the technical challenges of decarbonising aviation, but like Jennifer Lawrence’s character in Don’t Look Up, I just want to shout ‘BUT WE’RE ALL GOING TO DIE!’

And breathe…

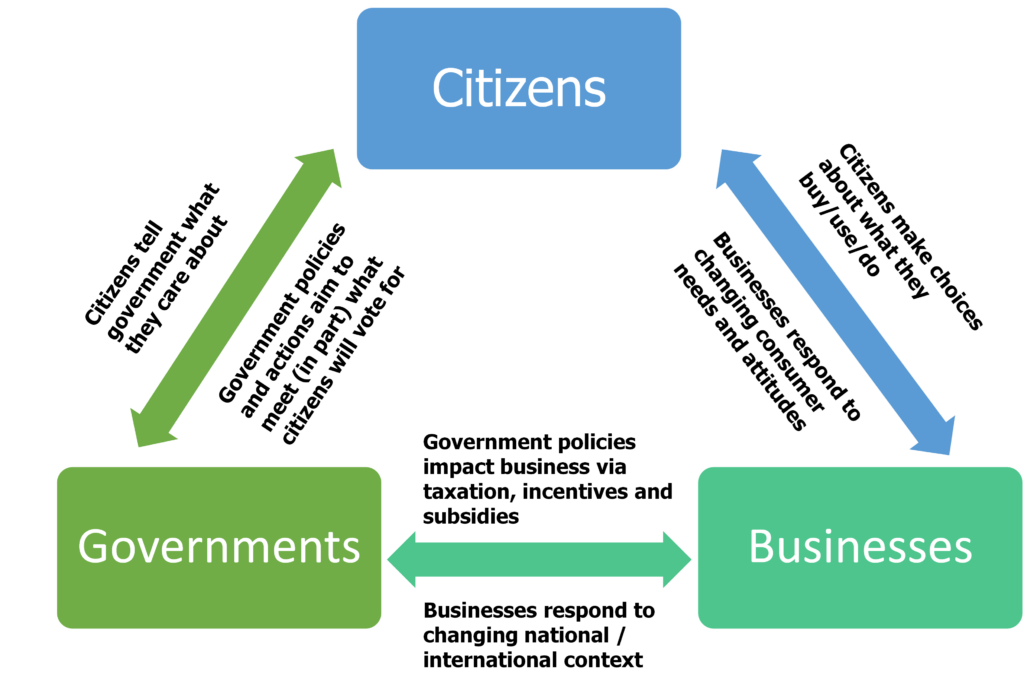

Anyway, amongst the personal resolutions about getting out and about more, away from my tediously covid-secure bunker, I think we need to find a new way to talk about climate change. Not in terms of doomsday but in terms of opportunity. Opportunity for different kinds of jobs in low carbon industries but also opportunities to live differently.

I can’t believe anyone really enjoys long commutes, traffic jams or cramming a two-week holiday in the sun into the middle of fifty weeks of drudgery. And we continue to worry about paying fuel bills because no UK government has yet tackled the real issue of energy self-reliance head on, when all along we have had wind and sunshine freely available!

So new beginnings but new ways of doing things. I don’t want to go back to business as usual. We can do better than that.